I found this on Ashley / Read All the Things‘s Blogger blog and really liked it, so here are my Book Oscars (note: I’ve slightly amplified the original list):

Best Actor (Best Male Protagonist):

The Prince of Denmark

— no question or competition.

The most complex character ever created in literary history, subject to fervent debate practically from the moment he stepped out of Shakespeare’s brain onto the Globe Theatre stage and finally onto thousands of other stages all around the world.

When precisely the realisation hit home with me what a truly unique character, and what a truly unique piece of writing Hamlet is, I can no longer even tell. All I know is that it was a gradual process: for a long time I was turned off by the Prince’s apparent wavering and by the play’s sheer length; as well as its gutwrenching atmosphere and – apparent – utter hopelessness, and in no small part also by its uncharitable stance towards its two female characters, Gertrude and Ophelia. Yet, eventually its unique power got through to me and firmly took hold of my brain, unmix’d with baser matter.

I collect Hamlet editions, both in print and on DVD — and I have, in recent years, created a website dedicated to my own interpretation of the play and, of course, the Prince’s character: Project Hamlet. The chances that I’ll ever be able to realize my vision of the play in real life are nil for all practical purposes, of course … but nevertheless one can dream, can’t one?

Runners-up:

- Fitzwilliam Darcy, as created by Jane Austen and as incarnated by Colin Firth in the 1995 BBC adaptation of Pride and Prejudice

- Thomas Cromwell, in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies (and you’d never have caught me even contemplating him for this category before I read Mantel’s books)

- Sherlock Holmes, as created by Arthur Conan Doyle and as incarnated by Jeremy Brett in the 1980s ITV series

- Lord Peter Wimsey, as created by Dorothy L. Sayers. (As to the TV adaptations, I’m on the fence — I love both those starring Ian Carmichael and those starring Edward Petherbridge.)

- * Brother Cadfael, as created by Ellis Peters and as incarnated by Sir Derek Jacobi in the 1990s TV series

Best Actress (Best Female Protagonist):

Lizzie Bennet, as written by Jane Austen and as incarnated by Jennifer Ehle in the 1995 BBC adaptation of Pride and Prejudice. Gotta love a young lady who can stand up for herself, even when facing the likes of a Lady Catherine de Bourgh!

Runners-up:

- Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre

- Ellinor Dashwood from Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility

Best Original Screenplay (Most Unique Plot or World Building):

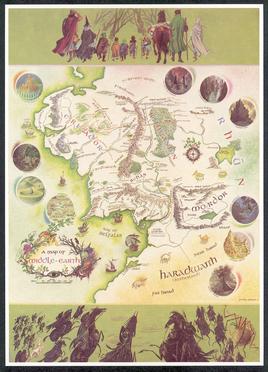

J.R.R. Tolkien‘s Middle Earth — over a decade in the making, complete with fully worked-out languages, cosmology, legendarium, maps, you name it. All of fantasy writing goes back to this (well, and to Narnia … but I prefer Tolkien).

A Map of Middle-Earth (Pauline Baynes, 1970)

Best Adapted Screenplay (Best Book-to-Movie Adaptation):

For sheer iconic value, I’m going to go with a joint award for the Humphrey Bogart adaptations of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep and Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon here. Two of the genre-defining noir novels adapted into two genre-defining noir movies — can’t get much better than that, can it? (Oh, and of course … Bogey. There’s him, too. And Bacall in The Big Sleep.)

Best Cinematography (Best Plot Twist):

A joint award going to the mothers of all plot twists: Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express and The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.

Best Makeup (Best Book Cover):

J.R.R. Tolkien: The Lord of the Rings

J.R.R. Tolkien: The Lord of the Rings

— 50th anniversary omnibus edition

I love its minimalist design, which nevertheless perfectly embodies and expresses the essence of the book(s).

Best Costume Design (Best Historical or Contemporary Setting):

Note: In the “Bookish Academy Awards” version I found on Ashley’s blog, “Best Costume Design” translates as “Best Book Cover,” and there is no equivalent / translation of “Best Makeup.” But I wanted an awards category for real-life settings as a companion to the “most unique world building or plot” translation of “Best Original Screenplay:” The latter, as I understand it, highlights the writer’s creative powers, and looks at something (s)he has conjured out of thin air and created from scratch. What I am thinking of in my version of “best setting” is how well a writer has managed to translate the nature of a real place or the atmosphere and lifestyle of a given historical period in their books — how well, in other words, they have “nailed” the real-life background and setting of their stories and make it come alive.

That all being said, the Oscar goes to … (drumroll) …

Hilary Mantel‘s Cromwell trilogy-in-the-making: Writing about the Tudor age may not necessarily be the authorial equivalent of Promethean fire in and of itself, but the way in which she makes 16th century London and English society, and the Tudor court, come to life before the reader’s eyes greatly enhances the narrative power of her books, and immensely facilitates the reader’s understanding of the characters — including and in particular Thomas Cromwell himself, who not so long ago used to be a fixture on the list of history’s most hated politicians, and whom her books, almost singlehandedly, have endowed with a heretofore unknown appeal to, and sympathy on the part of, modern-day readers. Surely without making the world in which he moved so transparent, she would probably not even have achieved half as much.

In fairness, though, in two of my favorite genres — historical fiction and mysteries / crime fiction –, as well as in their hybrid child (historical mysteries), “nailing” the setting is absolutely crucial to the success of every story (similar to the importance of imaginative world building in fantasy). And I’m also a particular fan of literary fiction and classics that essentially make their setting stand up and function as an additional character. So I’m finding it extremely difficult here, more so than perhaps in any other awards category, and also rather unfair, to single out just one author (and book series) to the detriment of all others. Thus, I hereby also give honorary awards to the books and authors listed in my separate post Sense of Time — Sense of Place, which brings together all of my favorite books and series with a particularly well-executed atmosphere and setting.

Best Supporting Actress (Best Female Sidekick or Supporting Character):

You know that tradition where they give a “supporting actor” award to someone who is actually just about as important to a movie as the winner of the “best actor” award? My “best supporting actress” winners fall firmly into that category. They are, on an equal footing:

- Portia, in William Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice

- Harriet Vane, Lord Peter Wimsey’s wife-to-be

- “The Woman:” Irene Adler from A Scandal in Bohemia; the only person to ever outwit Sherlock Holmes and be permitted to get away with it

Best Supporting Actor (Best Male Sidekick or Supporting Character):

Dr. John H. Watson — the godfather of all literary sidekicks

Runners-up:

- Jack Barak, Matthew Shardlake’s assistant in the series by C.J. Sansom

- Mervyn Bunter, Lord Peter Wimsey’s butler

- Archie Goodwin, Nero Wolfe’s sidekick, as created by Rex Stout and as incarnated by Timothy Hutton in the A&E series starring Maury Chaykin as Wolfe

Best Animated Feature (A book that would work well in animated format):

Hmm. Well, I think I’m going to go with Robert van Gulik‘s Judge Dee series here. Don’t know whether it’s because of the marvelous pen and ink illustrations by van Gulik himself (see, e.g., left) that are contained in the books, or because Judge Dee’s assistants do get to engage in quite a bit of martial arts, or because of both, but somehow it strikes me that these would translate quite well into an animated feature — provided the essence of the historical setting so faithfully and lovingly reproduced by van Gulik, which is an important part of what makes these books what they are, would adequately be maintained.

Hmm. Well, I think I’m going to go with Robert van Gulik‘s Judge Dee series here. Don’t know whether it’s because of the marvelous pen and ink illustrations by van Gulik himself (see, e.g., left) that are contained in the books, or because Judge Dee’s assistants do get to engage in quite a bit of martial arts, or because of both, but somehow it strikes me that these would translate quite well into an animated feature — provided the essence of the historical setting so faithfully and lovingly reproduced by van Gulik, which is an important part of what makes these books what they are, would adequately be maintained.

Best Director:

In the “Bookish Academy Awards” version that I’ve found on Ashley’s blog, the translation / subtitle of this category is “A writer you discovered for the first time.” But this one must needs go to my main man, Will Shakespeare, one of literary history’s most important writer-directors (in addition to his gazillion other merits) — as well as to his brain child, my other main man, the Prince of Denmark, who after all even gets to voice Shakespeare’s pains in reciting the man’s very own little acting handbook to the players come to Elsinore:

In the “Bookish Academy Awards” version that I’ve found on Ashley’s blog, the translation / subtitle of this category is “A writer you discovered for the first time.” But this one must needs go to my main man, Will Shakespeare, one of literary history’s most important writer-directors (in addition to his gazillion other merits) — as well as to his brain child, my other main man, the Prince of Denmark, who after all even gets to voice Shakespeare’s pains in reciting the man’s very own little acting handbook to the players come to Elsinore:

Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounc’d it to you,

trippingly on the tongue. But if you mouth it, as many of our

players do, I had as live the town crier spoke my lines. Nor do

not saw the air too much with your hand, thus, but use all

gently; for in the very torrent, tempest, and (as I may say)

whirlwind of your passion, you must acquire and beget a

temperance that may give it smoothness. O, it offends me to the

soul to hear a robustious periwig-pated fellow tear a passion to

tatters, to very rags, to split the cars of the groundlings, who

(for the most part) are capable of nothing but inexplicable dumb

shows and noise. I would have such a fellow whipp’d for o’erdoing

Termagant. It out-herods Herod. Pray you avoid it.

In other words:

1. Enunciate, enunciate, enunciate.

1. Enunciate, enunciate, enunciate.

2. Don’t chew your lines – or bellow them out.

3. Don’t gesticulate wildly and purposelessly. Remember that acting is (as the very word implies) about what you do as much as about what you say. Even moments of extreme passion are hardly ever expressed adequately by crude and exaggerated motions. To the playwright, there is nothing more painful than seeing a play’s most pivotal moments annihilated by coarse and uninformed acting. This is worse than even the most abominable stock characters we’re used to seeing portrayed as ranters, such as Muslim villains (Termagant) and King Herod.

4. Trust your instincts.

5. Perform naturally. Avoid stilted or forced behaviour – act on stage as you would in real life. Otherwise, you might come off as unintentionally funny; but only persons without any proper taste at all would laugh at such a performance. And your target audience aren’t those uneducated fools, however many of them there may be; your target audience are those who can actually appreciate a good performance.

6. Good acting isn’t a function of widespread public acclaim; it’s solely a function of talent and taste. One has absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with the other.

7. No ad-libbing! (You hear me, Will Kempe?!)

8. Self-indulgence is a vice, and the worst part about it is its infectuous effect on those in the audience who don’t know any better. Not to mention that it gets in the way of the play’s intended progress and diverts the audience’s attention from other, just as (or even more) essential scenes. That’s egotistical and countermands a truly great actor’s attitude – actors need to be team players.

London, Globe Theatre (photos mine)

Above left: Arend van Buchell: Copy of Johannes DeWitt’s sketch of the Swan Theatre, built in 1595 (original sketch lost)

Top left: Charles and Mary Lamb: Tales From Shakespeare — Hamlet and the Players

Best Visual Effects (Best Action in a Book):

Frederick Forsyth: The Day of the Jackal

… and he’ll always look like Edward Fox in my mind.

Runners-up:

Ian Rankin (writing as Jack Harvey): Bleeding Hearts

Ian Rankin (writing as Jack Harvey): Bleeding Hearts- Michael Connelly: The Poet — and most of the books from the Harry Bosch series have pretty good action finales as well

- Tom Clancy: The Hunt for Red October

- Thomas Harris: The Silence of the Lambs and Red Dragon

- Stieg Larsson: The Millennium Trilogy

- John Grisham: The Firm

- Trevanian: The Eiger Sanction

- George Pelecanos: Shame the Devil (and most of his other D.C. novels, too)

- Val McDermid: The Mermaids Singing

- Johannes Mario Simmel: Es kann nicht immer Kaviar sein (It Can’t Always Be Caviar)

- Akif Pirinçci: Felidae

Best Original Song (Best Song Inspired by a Book):

Mark Knopfler / Dire Straits: Romeo and Juliet

Best Original Score (Best Book / Series Incorporating Music as an Important Element):

Ian Rankin: The Inspector Rebus series.

Ian Rankin: The Inspector Rebus series.

John Rebus is a pretty big fan of the Rolling Stones and of Jackie Leven; in fact, both the Stones’ albums and Leven’s lyrics have provided several book titles, and the titles of songs that Rankin himself likes have made it onto book covers as well. But Rebus and his partner (or more recently: boss) Siobhan Clarke are frequently also seen listening to other music, or sparring off on their musical tastes.

For more, see my post, A Playlist for Ian Rankin’s Inspector Rebus Series

Best Short Film (Best Novella or Short Book):

George Orwell: Animal Farm

George Orwell: Animal Farm

Communism digested down to 100 pages in a parable and in language that even a child can understand.

Some animals are more equal than others.

Runners-up:

- Charles Dickens: The Christmas Carol

- Thomas Mann: Mario and the Magician

- Alexander Pushkin: The Queen of Spades

- Stephen King: Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption

Best Documentary (Best Non-Fiction):

Patrick Leigh Fermor: A Time of Gifts

Patrick Leigh Fermor: A Time of Gifts

The most poetic book ever written about an extended walk — and what a walk it was, too, all the way from the Hoek of Holland to Istanbul (well, OK; as far as the Hungarian border in this first instalment), in a Europe just on the edge of WWII.

Runners-up:

- Virginia Woolf: A Room of One’s Own

- Anne Frank: Diary

- Beryl Markham: West With the Night

- Ernest Hemingway: A Moveable Feast

- Tarnya Cooper and Stanley Wells: Searching for Shakespeare

- Jared Diamond: Collapse

- Thomas Keneally: Schindler’s List

- Willy Brandt: Erinnerungen (My Life in Politics)

- Hugo Hamilton: The Speckled People

Honorary / Lifetime Achievement Award (Overall Favorite Body of Work):

William Shakespeare: Sweet Swan of Avon, Soul of the Age — he was not of an age, but for all time. (Wholly agree with Ben Jonson there …)

Runners-up:

For my other favorite authors, see my About Me: The Less Random Stuff page.